Plato Theory of Justice

Justice has been one of the most debated concepts in political science, philosophy, and law. Among the earliest and most influential attempts to define it comes from Plato, the Greek philosopher of the 4th century BCE. His work “The Republic” is considered a masterpiece where he systematically explains what justice is, why it matters, and how it can be realized both in individuals and in society.

In this blog, we’ll explore Plato’s theory of justice in detail—breaking down its meaning, development, and lasting significance in political thought.

Background of Plato Theory of Justice

Plato lived in Athens during a time of political turmoil. The city had lost the Peloponnesian War, democracy was weakened, and corruption was widespread. His teacher, Socrates, was executed by the Athenian democracy, which deeply impacted Plato.

In response, Plato wanted to answer fundamental questions:

• What is justice?

• Why should anyone be just?

• Can a state be just, and what would it look like?

These questions shaped the dialogue “Republic”, where Plato (through the character of Socrates) examines justice as the foundation of both the individual soul and the political community.

Plato’s Method: Dialogue in “The Republic”

Plato does not give a quick definition of justice. Instead, he takes readers through a dialogue involving Socrates and others, where common notions of justice are challenged and redefined.

Initially, justice is defined in popular but narrow ways:

• Cephalus: Justice is telling the truth and repaying debts.

• Polemarchus: Justice is helping friends and harming enemies.

• Thrasymachus: Justice is the interest of the stronger (might makes right).

Plato rejects these views, arguing they are partial and self-serving. He insists that justice must be understood in a universal and moral sense, not merely as a social convenience or a tool of power.

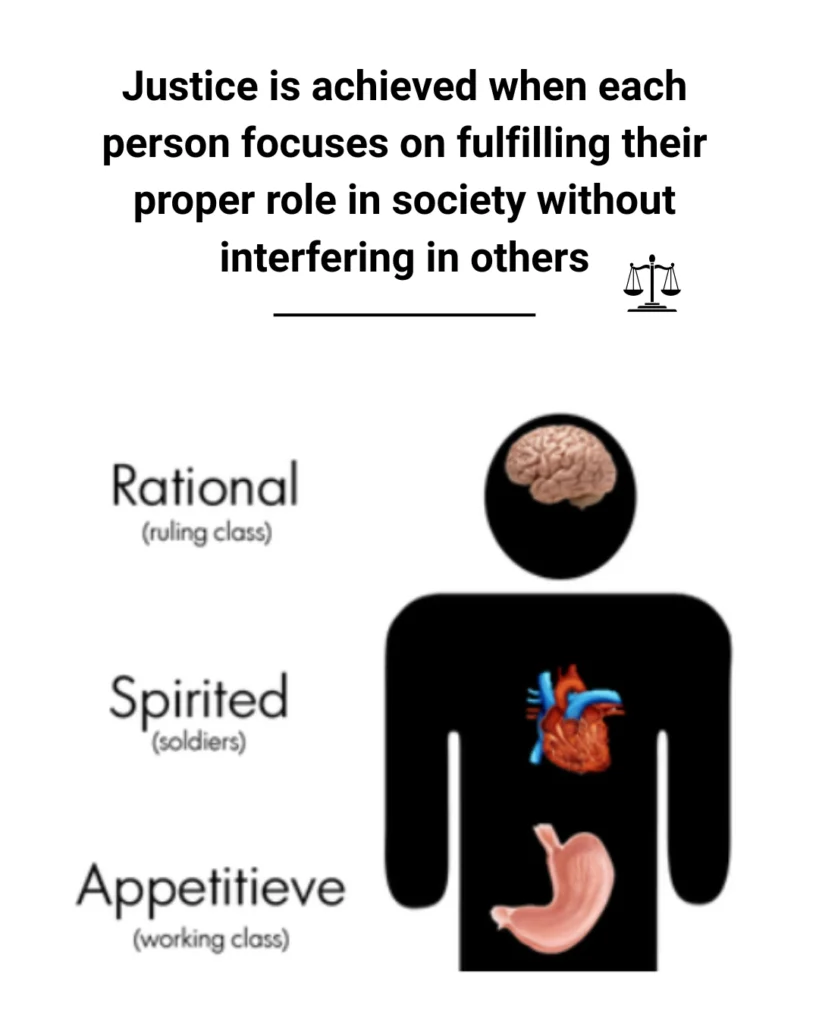

Plato’s Theory of Justice in the Individual

Plato compares the human soul to the state. Just as the state has different parts working in harmony, so too does the soul.

He identifies three elements of the soul:

- Rational Element → The reasoning part, which seeks truth and wisdom.

- Spirited Element → The part of the soul that seeks honour, courage, and defends reason.

- Appetitive Element → The desires and instincts (food, wealth, pleasure).

Justice in the individual means each part of the soul performs its proper function without interfering in the role of the others. Reason should govern, spirit should support reason, and appetite should remain controlled.

Thus, a just person is someone whose soul is harmonious and balanced.

Plato’s Theory of Justice in the State

Plato extends this idea to society. For him, the state is like a large individual, with different groups performing different roles.

He divides society into three classes:

- Rulers (Philosopher-Kings): The rational element, guided by wisdom, tasked with governing.

- Auxiliaries (Warriors/Guardians): The spirited element, responsible for defence and order.

- Producers (Farmers, Traders, Workers): The appetitive element, focused on economic needs.

Justice in the state means each class performs its own duty without interfering in the work of others. Rulers rule, auxiliaries protect, and producers provide.

Injustice arises when one class tries to dominate or take over another’s role.

Justice as Harmony

For Plato, justice is not about external acts alone (like obeying laws) but about internal harmony—in the soul and in the state.

• In the individual, justice is inner balance, where reason governs.

• In the state, justice is social balance, where every class performs its natural role.

Thus, justice is both a moral quality (inner virtue) and a political principle (social order).

Why Should We Be Just? Plato’s Answer

A central question in The Republic is: why should one be just if injustice sometimes brings rewards?

Plato answers:

• A just soul is healthy and harmonious, while an unjust soul is diseased and conflicted.

• Justice leads to happiness (eudaimonia), while injustice leads to misery, even if one gains wealth or power.

• A just state creates conditions for the good life, ensuring peace and cooperation.

So, justice is not only good for society but also essential for individual well-being.

Key Features of Plato’s Theory of Justice

- Functional Specialization: Justice means everyone doing what they are best suited for.

- Moral & Political Unity: Justice links ethics (individual soul) with politics (state).

- Opposition to Relativism: Justice is not just “whatever rulers say”; it has universal moral value.

- Harmony Over Equality: Plato valued harmony more than equality—he believed roles should be assigned by ability, not by birth or wealth.

- Philosopher-King as Ideal Ruler: Justice requires wise leadership guided by knowledge of the Good.

Criticisms of Plato’s Theory of Justice

While influential, Plato’s theory has faced criticisms:

• Authoritarian Tendencies: His idea of philosopher-kings seems elitist, concentrating power in the hands of a few.

• Rigid Class System: By fixing social roles, Plato’s state leaves little room for individual freedom or mobility.

• Neglect of Equality: Justice, as harmony, does not address modern ideas of rights and equality.

• Utopian Nature: Critics argue that Plato’s ideal state is unrealistic and impractical.

Despite these criticisms, Plato’s insights remain foundational in discussions of justice and political morality.

Relevance of Plato’s Theory of Justice Today

Even though Plato wrote over 2,000 years ago, his theory of justice continues to resonate:

• In debates on division of labour and specialization.

• In the idea that justice is not just law but also inner morality.

• In discussions of leadership ethics—should rulers be wise and virtuous rather than merely popular?

• In political philosophy classrooms, where Plato’s Republic is still one of the first texts studied.

Modern democratic societies may reject Plato’s rigid state, but they still grapple with the tension between individual freedom and social harmony that he so clearly outlined.

Plato’s theory of justice remains one of the most important contributions to political philosophy. For him, justice was not simply about legal rules or social customs but about the orderly functioning of both the soul and the state. His vision of justice as harmony—where every individual and every class fulfils its rightful role—offers a profound, though contested, way of thinking about morality and politics.

In our modern world, where justice is debated in terms of rights, equality, and fairness, Plato reminds us that justice is also about balance, virtue, and the common good. His ideas challenge us to ask: is society just when everyone pursues their own interests, or when all work together for harmony and truth?